Dystopia of Academic Publishing

“Trust the science” has become a ubiquitous mantra of today and it is arguably better than the available alternative. Setting aside the political undertones of this discussion, what this slogan is supposed to mean in practice is that results published in reputable peer-reviewed scientific journals should be treated as facts. These results dictate policy decisions, research trends and funding, and determine innovation waypoints on a global scale. As such, the academic publishing industry, which provides a platform to showcase peer-reviewed science, is a tremendously important space that deserves some scrutiny. Yet, it has remained unscrutinized and unchanged literally for centuries, with us - the academics - sleepwalking around the antiquated and often predatory publishing space.

The key value proposition of publishers is validation of scientific research, which elevates scientific conjectures into facts. This validation is accomplished via a peer review process, familiar to all published researchers. An ideal peer review process is supposed to involve a careful, deep, and unbiased analysis of results and data and to produce a referee report or reports assessing the importance, novelty, and correctness of the manuscript. Anybody familiar with the system knows that such a scenario almost never happens and there is typically little-to-no correlation between the intrinsic quality of a research paper and the outcome of its peer review.

Academic publishing is a tremendously profitable enterprise, arguably “discovered” as a business by Robert Maxwell – the father of both the science publishing industry and the infamous Ghislaine Maxwell. This industry boasts the profit margin of about 40% and the total accessible market of more than $20 billion. The business model of a for-profit publisher is insanely simple: researchers write papers for free, they referee papers for free, they work as editors for free or a nominal pay, and then they pay huge fees to read their own papers through corporate & University subscriptions. The typical subscription budget of a large state University in the U.S. is about $10 million, although it is hard to know exactly because most subscription bundles are under NDAs. Imagine any other business operating this way, say the restaurant business: The chefs buy ingredients using government funding, cook food for free, then tasters – other competing chefs – volunteer to anonymously taste each other’s creations and decide whether a dish goes to a Michelin star restaurant or McDonalds, and then the community all together pays a third-party private company an arm and a leg (an unknown amount) for access to their own food. The business model looks a little strange, yet this is exactly what is done in the current publishing system.

Pre-Robert Maxwell publishing had been delegated primarily to professional societies, where society members published their work. Many reputable old-school scientists used to read their relevant professional journals more or less in full. For example, Enrico Fermi reportedly read the Physical Review from cover to cover. It was possible because the information flow was manageable. For example, Richard Feynman published less than 100 papers over his entire career.

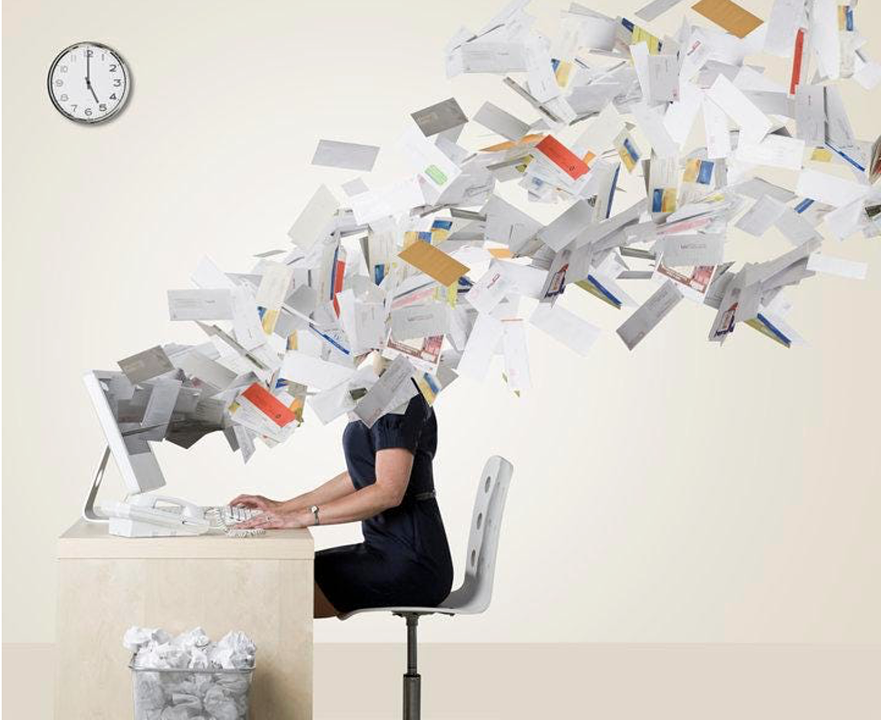

There are some prominent researchers in physics and other fields now, who publish more than a hundred papers every year. The data from arXiv.org shows an exponential explosion in monthly submissions. Outside STEM, the situation seems to be even worse. E.g., the number of papers with “COVID-19” in the title (which by definition only spans the last ~3 years) in medrxiv.org is more than 23,000. This corresponds to about a half-million pages of text and data. Assuming that it is just a regular text (e.g., a novel, which it is not), it would take a human about 1.5 years to read through this research with no breaks for sleep or food – just reading COVID-19 papers 24/7. It is clearly unreasonable, but the industry has no incentive to moderate this barrage of information, because the more there is to publish, the more the profit. On the contrary, new journals are created all the time with the total number of scientific journals being about 30,000 and growing.

In this age of information overload, many scientists find it difficult to not only follow others’ work but to even read their own papers (e.g., senior authors leading big groups and/or members of large collaborations). It would be naïve to think that the same researchers can find time to reflect on and professionally referee manuscripts in an unbiased way. These arguments and numbers all but prove that the peer-review system is broken, which is consistent with the heuristic experience and observations of most scientists, who complain about superficial and often biased reports. Another common complaint is that groupthink is rewarded, while originality is frowned upon.

To summarize, science is currently experiencing information overload where it is no longer humanly possible to meaningfully follow research progress even in highly specialized fields and where peer review means little. It is becoming more and more difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff and there is little doubt that some gems are lost within this noise. This situation will undoubtedly be exacerbated by recent (otherwise exciting) developments involving natural language processing AI engines.

Not only the current publishing system seems counter-productive, but it is also disliked by almost all participants in the process – the authors, the referees, and the editors. A reasonable question is why are we doing it to ourselves? The answer is of course the publish-or-perish culture and the pressure from the system. To be competitive in getting a tenure-track job, promotion and tenure, students & postdocs, and research funding requires an extensive publication record. Since the metrics used to assess one’s research are mostly quantitative and rather superficial (number of publications, citations, impact factor of journals, h-index etc), this forces us to publish, publish, publish and to conform research to the requirements of prestigious journals (which almost invariably involves dumbing down the content to meet the broad impact and accessibility criteria). This leads to a dubious choice between the rat race of publishing superficial pieces non-stop or publishing less but risking to lose funding, students, and relevance. It is unclear how to get out of this trap, but it is probably time to start looking for an alternative publishing format and an alternative incentive structure in science, so that it can be trusted again.

Victor Galitski

Professor, Joint Quantum Institute, Univ. of Maryland (all views are my own)

Victor Galitski

Professor, Joint Quantum Institute, Univ. of Maryland (all views are my own)